As a Business Analyst, one of our primary task is to facilitate the process of defining the right problem. A well-defined problem statement is the compass for the entire project. Misunderstanding the core issue leads to building an elegant solution to the wrong challenge, wasting time, budget, and credibility. This foundational step is critical: studies show that up to 70% of project failures are attributable to poor requirements gathering, which often stems from an incomplete understanding of the initial business problem.

This post breaks down the best practices for moving beyond surface-level complaints and creating clear, actionable problem documentation that aligns stakeholders and guides development.

Phase 1: Understanding the Root Cause (Discovery)

The greatest mistake a BA can make is treating a pain point as the problem. “We need a faster reporting system” is a pain point; the underlying problem might be “Manual data aggregation across four siloed systems leads to a 48-hour delay in monthly reporting, resulting in missed investment opportunities.”

1. Differentiate Pain Points from Root Causes

Pain Points are observable indicators of user friction (e.g., high customer complaints, slow process times). The Root Cause is the deepest factor that, when removed, prevents the recurrence of the undesirable outcome.

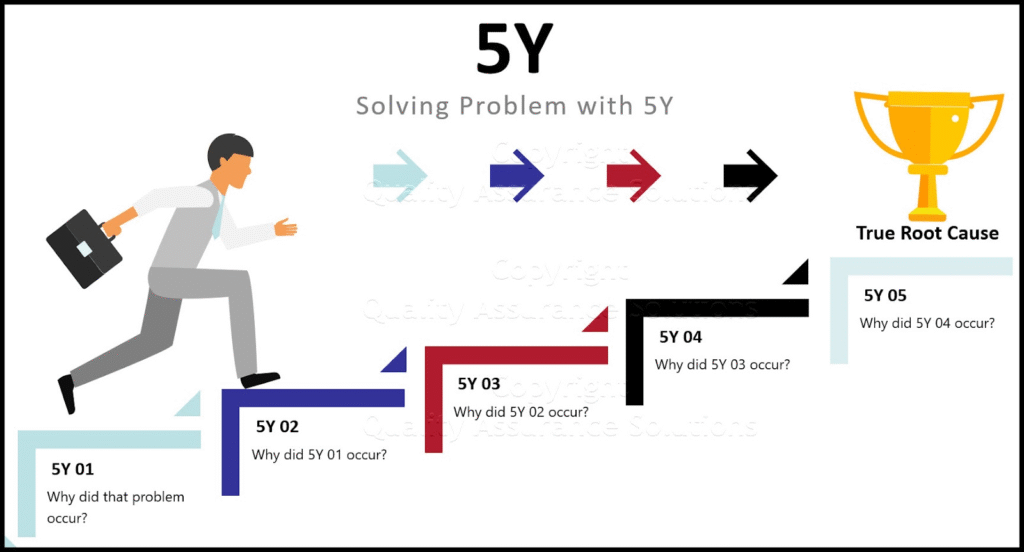

- Technique 1: The 5 Whys: Start with the pain point and keep asking “Why?” until you reach the fundamental driver.

This simple but powerful technique strips away assumptions and focuses on process failures rather than blaming individuals.

Pain Point: System downtime is too high.

- Why? The server crashes frequently.

- Why? It runs out of memory.

- Why? The nightly batch job consumes excessive resources.

- Why? It processes all records instead of only new ones.

- Root Cause: The job logic is inefficient and runs unnecessarily long.

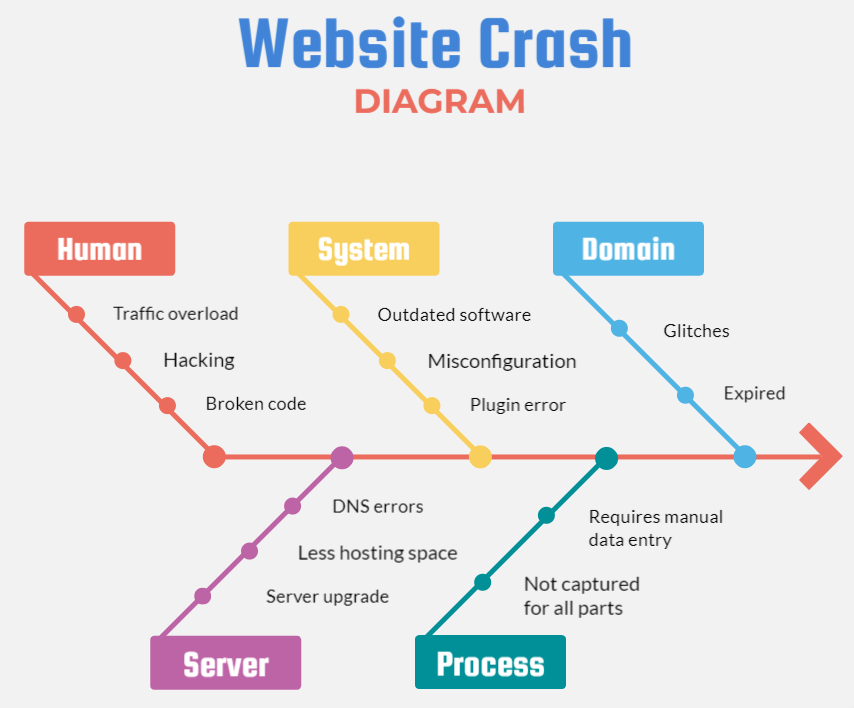

- Technique 2: Fishbone (Ishikawa) Diagram: Use this tool to visualize potential causes by categorizing them (e.g., People, Process, Technology, Environment, Measurement). This is excellent for complex issues where multiple inputs contribute to the same outcome. It ensures you have considered all possible contributing factors before settling on a final root cause.

2. Identify and Engage Stakeholders (The “Who”)

A business problem is rarely confined to one department. Interview and observe users from all affected groups to gain a 360-degree view. Ignoring key stakeholders often leads to scope creep or the failure of the final solution due to low user adoption.

- End-Users: They experience the pain daily; they know the how and can define usability needs.

- Managers: They understand the performance metrics and business impact; they know the cost and define operational requirements.

- Executives/Sponsors: They define the strategic goal; they know the why (the high-level value) and sign off on project prioritization.

Pro-Tip: Prioritize Engagement with the Power/Interest Grid. Categorize stakeholders based on their influence (Power) and their concern (Interest) regarding the problem. You must heavily manage those with High Power, High Interest and keep those with High Power, Low Interest satisfied with minimal updates.

3. Quantify the Pain (The “Cost”)

A problem that cannot be measured cannot be justified for fixing. Always document the current state in measurable terms. This quantification transforms the problem from an observation into a business case.

- Weak: “Our invoice approval process is slow.”

- Strong: “The manual invoice approval process takes an average of 5 business days, resulting in a penalty cost of $15,000 per quarter due to late payments.”

Quantification should target several key areas (Key Performance Indicators or KPIs):

- Time: Cycle time, average handle time (AHT), time spent on rework.

- Cost/Financial: Penalty fees, lost revenue, material waste, labor hours spent on manual tasks.

- Quality/Compliance: Error rates, non-compliance fines, number of defects.

- Customer Satisfaction: Churn rate, Net Promoter Score (NPS), complaint volume.

Phase 2: Documenting the Problem (Artifacts)

Once you understand the root cause and have quantified its impact, you must formally document it. These artifacts ensure alignment across the development, business, and executive teams, acting as the single source of truth for the project’s purpose.

1. The Formal Problem Statement (The Core Artifact)

This is the single most important paragraph in your documentation. It should be concise, powerful, and tell a complete story. It acts as the executive summary for the entire problem analysis.

| Element | Description | Example |

| The Who | Who is affected? | Our Customer Support team… |

| The What | What is the pain/problem? | …is manually copying ticket data… |

| The Impact | What is the cost of the problem? | …leading to a 20% error rate and increasing average resolution time by 3 hours. |

| The Opportunity | What is the goal of fixing it? | Implementing an automated data feed will reduce the error rate to below 5% and save the department 120 man-hours per month. |

2. Current State vs. Future State Analysis

This documentation provides essential clarity on the scope and extent of the change. It defines what exists now (the baseline) and what is being targeted for the solution (the goal).

- Current State (AS-IS): Document the existing process flow, actors, technologies, and constraints. Use standard modeling notations like BPMN (Business Process Model and Notation) or simple AS-IS flowcharts to illustrate the exact steps where the process breaks down or where delays occur. This visual model should make the current pain points undeniable.

- Future State (TO-BE): Document the desired outcomes and processes. The TO-BE model must show a measurable improvement from the AS-IS state, reflecting the elimination of the root cause. This is where you begin defining the new system capabilities.

- Gap Analysis: Explicitly state the differences between the AS-IS and TO-BE states. The Gap Analysis is the blueprint for your requirements, identifying the capabilities that must be built, acquired, or decommissioned to bridge the distance between the two states.

3. Defining the Scope & Context

A well-documented problem must be constrained by a clear scope. You must explicitly define what parts of the organization or system are in scope and, equally important, what is out of scope to prevent uncontrolled scope creep.

- Context Diagram: A high-level visual that places your proposed system at the center and shows all external systems, data sources, and user groups that interact with it. This is crucial for developers and architects, as it quickly establishes the boundaries and dependencies of the problem space, especially concerning necessary system integrations.

- Scope Boundaries: Ensure the scope includes not just functional requirements (what the system must do) but also non-functional requirements (e.g., the performance target must be ‘Response time under 2 seconds,’ or the security requirement is ‘Must be HIPAA compliant’). These constraints are often tied directly to the impact metrics identified in Phase 1.

Conclusion

The Business Analyst serves as the detective, historian, and translator for every project. By rigorously employing root cause analysis, quantifying the current pain, and structuring your findings into a clear, measurable Problem Statement, you ensure that your team is always building the right thing. Focus on clarity, collaboration, and measurable impact, and your projects will start on a foundation strong enough to support successful delivery.